DIAGNOSIS REPORT

CHAPEL HILL DEVELOPMENT ORDINANCE

INTRODUCTION

This review addresses several topics in three sections. The first section reviews the general organization and structure of the code. The emphasis on this review is to help produce a user-friendly document. The second section reviews the substance of the code. The code is 19 years old; certain elements may be outdated or have better alternatives. The third section focuses on additional concerns identified by the Town, including staff, citizens, and advisory boards (see Appendix A for a summary).

In terms of overall organization, our emphasis is on making the ordinance “user-friendly” through plain language and simplicity. However, Chapel Hill has numerous goals it seeks to achieve with its development regulations, which may sacrifice some simplicity. The more goals the ordinance takes on, the more complex it will become. An important question arises: “For whom should the ordinance be written?” Citizens wanting to know the degree of protection afforded by zoning, or business persons seeking to expand, may never have picked up the Chapel Hill ordinance; thus, they can be easily confused. Staff, planners, developers and lawyers who use the ordinance frequently know the ordinance almost by heart. Professional planners and attorneys in communities with the most confusing ordinances become expert in their use, so these professionals are less critical. A good way to manage this difference in use is to identify sections of the ordinance that the average citizen is most likely to use and make these sections easily accessible. Sections used by professionals on a regular basis should follow these sections, and be structured in a logical fashion so rarely used elements can also be easily located.

Our general review will look at technical problems identified by the Town, appointed officials, citizens, and the consulting team. Appendix B contains a full copy of the comments received from various groups. We will look at how other communities handle various topics and compare them to the approach found in the Chapel Hill ordinance. An important element will be the assessment of definitions, uses, and other elements in light of today’s market conditions.

The third section of our review will address additional concerns raised by the Town, including mixed-use districts, low-impact development regulations or incentives, land use intensity ratios (LUI), and the impact of the regulations on housing affordability.

ORDINANCE ORGANIZATION AND READABILITY

General Structure. The Chapel Hill Development Ordinance has 24 articles[1] in a combination of what used to be separate zoning and subdivision regulations. The organizational structure is weak. For example, use regulations are contained in a use article (Article 12) and also in several zoning districts, such as mixed use. The non-conforming article separates process-oriented sections, such as amendments and enforcement. For the casual user, the current organization places the most desired information (i.e. what a person can do with his or her land and how intensely it can be developed) in the middle of the ordinance. These two articles should be among the first. The existing ordinance’s first article contains general provisions that are largely legal boilerplate, which could easily be moved to the rear with the “Legal Status” article.

To be clear to first-time users and logical for experienced staff, land use, intensity, and lot size information should comprise the first part of the ordinance. These are the most needed and frequently used sections and should be readily accessible. The second part of the ordinance should deal with supplementary zoning issues. The third part of the ordinance should address subdivision and design regulations. Administration and legal boilerplate should comprise the fourth part of the ordinance, and definitions are best at the end.

Definitions. “Definitions” is the second article of the ordinance, but definitions are found throughout the ordinance. All definitions should be in the definitions section to avoid error when the same language is in different places. For example, “outdoor space” is not defined consistently in the definitions and land use intensity sections. Sometimes the definitions are contained only within a subsection (i.e. “outparcel”). Definitions in most books are found in the rear, and that practice should be followed in development ordinances, as well. With the computerized zoning ordinance (CZO), defined terms can also be accessed via a “hotlink” making it easier for the user.

Secondly, there are some substantive problems with existing definitions. Some definitions are obsolete, because land uses have changed. Other critical definitions are at the heart of important land use issues, and need to be revised. “Dwelling unit,” “family,” “group living,” and “rooming houses” are examples of a series of related definitions central to the ability of the ordinance to meet community goals. “Open space” is another example of a definition that must be written specifically to achieve the Town’s goals and objectives.

A third problem with the definitions is that they often include regulatory language. The definitions of “home occupation,” “mobile home,” and “outdoor skateboard ramp” have regulatory language mixed into the definition. This is a serious obstacle to user-friendliness. Regulations should easily be found in a single place or in specific topical sections (i.e. “tree protection” and “landscaping”). Lastly, in some newer ordinances, a subset of definitions is “rules of measurement.” This provides all measuring techniques in a single location.

While the ordinance does a good job of grouping similar definitions (i.e. “street,” “street, public,” “street, private,” etc.), some improvements are possible. Cross coding definitions needs to be done. (Cross coding refers users to definitions.) For example, the definitions would contain: Public Street. See Street, Public.

Font. One very easy improvement is changing the font. Architects and planners have become fond of sans serif fonts, but they are not found in books or newspapers, and readers are not used to them. Going to a serif font will make the document easier to read.

Illustrations. The current ordinance contains some illustrations, but its clarity can be significantly improved with more illustrations. This is particularly true in the definitions section.

Tables. The use and LUI sections of the ordinance use tables. These can be improved upon by making the tables as complete and simple as possible. In some cases, text can be replaced with tables. The duties and procedures of boards (Planning Board, Board of Adjustment, etc.) are repetitive. While the membership and quorum are different, a table can deal with this succinctly.

GENERAL REVIEW

Our review identifies issues beyond those in the request for proposals. Some are related to simplification and making the ordinance more user-friendly. Others are substantive issues that will require new or revised standards.

Districts. The present ordinance has 30 districts and overlay districts – more than needed. There are eight single-family districts, some of them created only to address existing developments. The single-family districts generally permit the same uses and could be combined into a single-family district or neighborhood conservation district permitting the same uses, with a number that indicates the lot size. The two Town Center (TC) districts differ only in the maximum height limit; this standard does not warrant a separate zoning category and can be controlled in the table of dimensional requirements. The Institutional/Office districts are also candidates for consolidation. We need to look at whether the differences in permitted intensities can be related to other criteria and, thus, avoid the use of two separate zoning categories. Both of the Mixed Use districts will need to be replaced because the type of development the Town is getting has not lived up to expectations. The overlay districts are also candidates for consolidation or elimination (see Low Impact Development and Environment).

Special Uses. We received differing messages on special uses. Some people suggested that there should be more special uses, because this provides for more citizen input. Others felt that there were already too many special use applications. Strongly related to the special use issue is the concern that the current development process is too adversarial.

There are three basic strategies for addressing uses. In the first zoning ordinances, uses were simply permitted or prohibited. This traditionally did not provide flexibility to address somewhat difficult uses. For a use that ultimately was desired but not permitted, the method to address this was to change the zoning to a district that permitted that use. Next came the special use permit. The special use permit is a procedure by which the Town Council, after public hearing and recommendations from the Planning Board, may approve the use and, if desired, attach specific conditions. The third approach is the use of performance standards, which permits uses by right, subject to certain performance criteria.

The permitted/prohibited scheme of zoning is basic. Often, districts are created to control certain troubling uses, requiring developers to seek a zoning change to accommodate their proposed use. The major problem with this approach is that it never directly addressed the problem use. It relies on the zoning hearing process to make an appropriate decision. In recent years, an alternative form of permitted use, the limited use, has been included in many ordinances. The limited use, like the permitted use, is permitted as a matter of right. The difference is that the limited use has standards attached that must be met. These standards address location, separation from specific types of uses, minimum or maximum site areas, building scale conditions, bufferyard requirements, architectural details, and other design requirements. The result of the limited use standards is that while a use is permitted in a given district, it may not be possible to build that use on every property within the district. This approach is performance-oriented because it directly targets impacts and develops standards to address them. It is cost-effective because effort goes into the initial development of the limited use standards and is not repeated for every application.

The special use approach is entirely process-oriented. The goal of the special use process was to provide flexibility through contextual review. As initially envisioned, most applications would be approved with a few conditions, and only a few proposals would be denied. The theory, unfortunately, does not correspond to what happens in actual practice. A special use approval is a negotiated decision. The first rule of negotiating is to begin from a position from which one can retreat to a compromise. Both the developer and the local government are, thus, encouraged to make excessive demands so as to have elements to give up during the negotiating process. This immediately creates an adversarial hearing process. From a planning perspective, a negotiated process means that the developer cannot afford to initially propose his or her best plan – the local government is, thus, spending time reviewing a second-rate plan. The original special use process envisioned that planning staff would make appropriate recommendations to better protect nearby uses. It did not take long for the public to take on this role as well, become the third party in the hearing process. All too often, neighbors are simply opposed to the project. They prefer that the land remain undeveloped, substantially increasing the adversarial nature of the process. This is the most time-consuming mode of decision-making. It is costly for all parties: town, developer, and citizen. Worse yet, it is inconsistent.

A performance zoning approach begins with identifying relevant public purposes, such as protecting neighbors, the environment, or a community’s character from adverse effects of development. The ordinance is then written to protect these important interests. For example, glare from gas stations lit to operating room standards is a nuisance. A performance ordinance would have specific lighting standards that require cut-off fixtures and set the maximum illumination at a residential property line. This directly addresses the concern with a specific regulation. Many of the standards like lighting, noise, vibrations, environmental protection, signs, bufferyards, and landscaping are applied community-wide. In other cases, the limited use standards discussed above are used to deal with specifically troubling uses, such as drive-through facilities. In a performance ordinance, most uses are permitted, with a high percentage of limited uses and very few special uses. Performance standards are designed to achieve public purposes and permit the landowner the maximum flexibility to meet market demands. This system is very consistent: the standards have to be met, or the project does not go forward.

We believe that there are too many special uses in the current ordinance, and that the community would be better served by performance standards. Citizens can review the performance standards during the drafting phase to determine if their concerns have been addressed.

Process. Many of the process-related concerns cited by various groups are related to the dependence on special uses. However, there are other process issues as well. There needs to be common sense remedies where a minor change is needed. Who should review such changes--the Town Council, Zoning Board, or staff? Each group offers a different type of review. The appropriate agency for decision-making and the related cost and complexity of a review must be weighed against any threats to the public interest. Many ordinances contain standards that permit staff to make minor adjustments in accordance with specific rules, reserving the more difficult decisions for a higher level of review. Some ordinances are defining the level of accuracy to within a foot to eliminate such problems.

The length of time to get approvals has also been criticized. We will review this further to determine whether other streamlining and the reduction of special uses largely eliminates the problem.

Use Classifications. The use classifications are well done, with few uses and broad categories. However, the three use categories may be an unneeded classification that increases complexity with little or no benefit. Churches and bars were identified as conflicting land uses that might need separation standards. Drive-in/Drive-through uses are typically seen as a potential problem. The concern about specific use conflicts has potential to create problems for mixed use areas. Advocates of traditional town planning and mixed uses argue for the elimination of restrictions on uses.

Student Housing. Student housing is a problem in every college town we know. The university can’t meet all the housing needs of its students on campus. Some will therefore look for housing off-campus. At the same time, the Town must protect single-family neighborhoods. The tools used to protect single-family neighborhoods are typically the definition of family, high-density housing designed for students, and multi-family housing. Single students living at higher densities will out-bid other households. A restrictive definition helps constrain this somewhat, but is complicated by the presence of protected classes that must be permitted to occupy single-family units with no special treatment. Maintaining these protected classes while controlling student rentals can best be done by a using a “group home” use that is permitted identically to single-family, but its definition rules out student housing, rooming houses and other non-family housing. In the category of “the best defense is a good offense,” we believe encouraging off-campus student housing close to the University will take the pressure off other neighborhoods.

OI-3 and MX-150 Zoning. These districts, one existing and one proposed, deal with University land. The University has reached capacity in the OI-3 district and is preparing a master plan with a 30% increase in total floor area on campus. The MX-150 zoning was begun several years ago and was then put on hold. To advance these projects, Town and University will need to see mutual benefits. The University will need to continue to grow and expand facilities, but cannot do so if it adversely impacts adjoining neighborhoods. Further, management of parking, transportation, and student housing are all important issues. While ultimately this is a zoning issue, it is first and foremost a planning issue. Writing the regulations for both districts will be straightforward once everybody agrees to a master plan for the central campus and the Horace Williams tract. From the Town’s point of view, residential neighborhoods need protection, traffic management and transit service are critical, and plans must be environmentally sensitive. Large increases in total floor area cannot be permitted to lower water quality and the campus should set the standard for environmentally sensitive design.

Commercial Parking. Some of the existing parking standards are no longer consistent with national standards. The problem in Chapel Hill is that land uses in the Town Center cannot provide the needed parking for commuters, while the Town is attempting to create a pedestrian environment where automobiles are discouraged. Student housing creates another parking issue when students come to Chapel Hill with automobiles and are not able to park on campus. New mixed-use centers will also have parking needs in excess of what the Town would like to see. This is an issue for many communities. It is easy enough to lower the required parking standards to a level that makes parking difficult during peak parking demand. Many older large cities have experience with obsolete parking standards. Their experience is that developers want or demand more parking than the minimum required. Can the Town mandate a parking maximum? Yes, that is possible, but how will the market react to such a maximum standard? If the developers believe there is a market in Chapel Hill that cannot be met at another location, they will build and provide less parking. But if the developer has a choice of locations, he or she may elect not to build in Chapel Hill.

A less draconian measure than an absolute cap is an initial maximum with a reserve area. The developer may then land bank area for future parking (or for building expansion; if the parking is not used, land banked parking areas could be built out only if the Town finds the initial parking to be inadequate). The Town sets the standard for increasing the parking. The developer must acquire more land than is needed by ordinance to provide the land bank or be prepared to provide structured parking, creating an economic cost for the user. To make this work, the Town needs to ensure that it maintains an enhanced transit service so that use of public transportation is encouraged. It may also want to mandate that uses selling large products (requiring the buyer to bring a car) offer same-day delivery.

Currently, the Town controls parking by collecting fees in lieu of parking, allowing off-site parking, and using a lower parking ratio. It does not count on-street parking. The ordinance should count on-street parking in the Town Center and other areas where it wishes to reduce the use of land for parking. Typically, this leads to a 5-15% reduction in on-site parking. The ordinance would identify “parking service areas” and maintain a count of on-street or Town parking lot capacity. These spaces would be allocated on a per-acre basis to all landowners wanting to develop in the parking area.

Yet another approach is for the Town to calculate maximum floor area in a zone such as the Town Center and agree to maintain a certain level of parking, thus permitting land uses to provide a much lower level of parking because of the Town’s policy of maintaining a certain level of parking. A variation on this is for the Town to identify priority uses in an area and let them build to a much lower or non-existent level of parking, while making other uses provide normal parking. Off-site, shared parking for multiple users in a central garage is another alternative.

Residential parking. Parking is also a problem with student housing. Controls are needed to ensure parking is present before a permit is issued, and the parking must not be a potential nuisance for the neighborhood. The use of valet parking needs to be explored further.

The Town has relied heavily on the special use process to provide a platform for neighbors to become involved in protecting their neighborhood. Some commented on even more access. This runs counter to the notion of making development decisions less adversarial. The primary focus should be ensuring that design standards in the ordinance address the legitimate concerns of adjoining property owners.

ADDITIONAL ISSUES

Four major issues have been identified for particular study:

• Mixed-use districts,

• Low-impact development regulations or incentives,

• Land Use Intensity ratios (LUI), and

• Impact of regulations on housing affordability

Mixed Use. Mixed use developments concentrate work, shopping, and living facilities in a small area to permit people to walk or bicycle, rather than force them to drive to all activities. The purpose statements of the current mixed use districts identify this basic objective. However, the regulations have only created developments with a variety of uses that remain separated much as they would have been if the land were conventionally zoned. The current ordinance does not require a residential component (in both mixed use districts, there is an option to provide only a mix of Office and Commercial). More importantly, the current ordinance does not address vertically-mixed uses, the most desired application of mixed use development.

The term “mixed use” has been around for a long time in the planning profession. As in Chapel Hill’s ordinance, most early mixed use provisions provided for mixed use within the development where the uses were separated horizontally across the property. The Chapel Hill North development pictured below is typical of horizontal mixed uses. The more recent concept of mixed use is a vertical distribution of uses. Thus, ground floor uses could be retail commercial or service businesses, while the upper stories would be office or residential. While modern mixed use does not rule out horizontal mixing of uses, it clearly envisions that commercial uses and a significant portion of employment uses would be located in mixed use structures. The ordinance should require some portion of the mixed use project to be vertically mixed. The intensities of use must be great enough to economically justify the vertical mixed use structures.

|

|

||

What is the appropriate location and purpose of the mixed use districts? Several of the mixed use zoned areas were clearly envisioned to be interstate-oriented business parks. A different area is planned as a neighborhood shopping and business area serving the surrounding planned residential community. The town center is another designation that currently makes use of the mixed use concept, and here, unlike the mixed use districts, there are several examples of vertical mixed use.

We suggest more encouragement of mixed uses in several districts. In office/institutional and industrial districts, mixed uses should be allowed as long as they don’t reduce employment potential. Some retail and service businesses in these districts will reduce automobile trips and should be permitted. Most mixing in such districts will be horizontal, but could be vertical. The mix can be controlled by limiting the percent of the retail or service uses. In addition, there could be incentives of increased floor area for multi-story mixed use projects which involve residential uses.

In the Town Center, mixed uses may be encouraged by parking requirement reductions and increased height and floor area limits. Such revisions would be consistent with the goal of making the Town Center a dynamic, pedestrian-oriented environment. A second mixed use area might be transit-oriented development. Infill development along transit corridors should encourage densities and uses that encourage pedestrian traffic in the immediate area, and should encourage commuting into the Town Center or University. This type of district would be mostly vertically mixed.

|

|

||

Last, the neighborhood commercial district is ideal for mixed use. Southern Village is a good application of mixed use. The conversion of the neighborhood commercial district to a mixed use district should be considered. Another alternative is to permit a mixed use center in large-scale residential developments.

The scale of mixed uses is also an issue. Some people suggested that mixed use be allowed to occur on smaller parcels. This scale concern is also related to issues with student housing and land uses in transit corridors.

Low-Impact Development and the Environment. There is a general desire to strengthen the environmental standards in the ordinance. The recent flooding has heightened this concern. There is interest in the conservation development concept of Randall Arendt. Conservation or low-impact development seeks development that is more sustainable, allowing the natural environment to function to enhance the quality of the developed environment.

Chapel Hill’s ordinance deals with floodplains, water quality, storm water management, and tree and slope protection. These sections should be strengthened. Storm water management is an example. Until recently, a ten-year storm was the design storm; now, the Town is using a 25-year storm. In many urbanizing areas, however, the design storm is the 100-year storm. In the most advanced ordinances, the storm water release rates are lower than the pre-development rates.

The watershed protection district has two standards. The low-density option permits 24% impervious surface, a value that comes from the State’s mandated watershed protection. However, experience indicates that above 10% impervious surface, a watershed suffers symptoms of declining water quality. The Center for Watershed Protection reports that when impervious surfaces exceed 10%, streams are negatively impacted, with unstable stream banks, erosion, channel widening, and poor physical habitat contributing to declining biodiversity. When watershed impervious cover exceeds 25%, streams become non-supporting, meaning that they are solely a means of conveying water and cannot support a diverse stream community.[2] The existing low-density standards approach the “non-supporting” level of stream health.

All larger developments in watershed protection districts should use wet detention. Detention can be provided project by project, house by house (with water gardens), or on a small watershed basis. The small watershed basis is generally thought to be superior, because they can all be wet basins and are larger and easier to maintain. However, watershed retention requires active government participation and management. Most large developments should be required to provide wet basins. Smaller developments are the most difficult to manage for water quality. Individual homes or small commercial uses may use water gardens and get good water quality benefits.

In addition to impervious surface, a significant element of water management for both quality and quantity is the type of land cover. Forest and natural grasslands are superior to lawns. Some communities are requiring lawns to include plant types that are not watered or fertilized. Chemically treated lawns are a significant source of potential pollution. Another water management concept is to require a natural buffer along a waterbody (or streams leading to the waterbody). A forested stream buffer with no lawn is the best buffer. Buffers can range from 25 to 300 feet wide.

The water quality district overlaps with the watershed district. If the watershed district is good, there is no need for the water quality district. That district does not impose standards on single-family or two-family zoning, so it misses the majority of the Town’s zoning. Further, the standard is subjective. What does “it is desirable to encourage” mean? If there is not a firm standard for infiltration, then developers do not know what is expected and the Town can only try to arm-twist developers.

The resource conservation district (RCD) contains two resources, the floodplain and a stream buffer. These two can overlap. The district is confusing because the areas are not defined in a mutually exclusive manner. What would normally be considered floodplain is extended by two feet in elevation; this area is actually functioning both as a floodplain and a buffer. The stream buffer area of 75 or 100 feet can include floodplain areas and, in some instances, could lie entirely within a floodplain. Wetlands, forests, drainage ways, and steep slopes are other resources that are not covered in the resource conservation district. The ordinance permits some impervious surface uses within the floodplain; this is a mistake unless the use is water-dependent, such as a boat ramp. Infrastructure should also avoid these areas, and the Town must be rigorous in seeking to limit road or utility crossings.

The ordinance should specifically include wetlands as a resource conservation district area with the same protection level as floodplains. There is no reason uses should be permitted in either of these areas, except for essential crossings of these areas. If there is flood damage on a regular basis to structures in the floodplain, the Town should work with appropriate Federal officials to relocate the structures. This should be built into the standards.

While the ordinance has sections on tree preservation and steep slopes, these sections are subjective and weak. The strongest ordinances set strict standards for development on steep slopes or forested areas. The second tier of tree protection ordinances relies on mandatory replacement of trees cut. Other steep slope regulations require geotechnical reports; however, these occasionally result in overbuilding and subsequent problems. Few significantly reduce the level of development on steep slopes.

There are several options for making the ordinance more environmentally sensitive. The current standards can be reviewed individually. This might result in expanded or additional overlays. The disadvantage of this approach is that it involves many districts and it is difficult to see the overall relationship between the sections. A second, performance-oriented approach builds a full environmental system that requires environmentally sensitive development and adjusts density based on the environmental constraints that exist on a site. A third approach is to look for development practices that are environmentally sensitive and integrate them into the code. There is a choice to be made between the first and second approach, but the third approach could enhance either choice.

A performance-oriented conservation approach requires the developer to begin the development process with an analysis of the resources that are present on the site. Performance ordinances have clear standards for protection and provide specific calculations that identify the maximum capacity of the site. This eliminates negotiating how much environmental protection is needed, as is the case with subjective standards. Performance regulations make planned or cluster development permitted uses, so that developers are free to cluster to avoid a density penalty. The intensity levels for single-family, cluster, or planned developments are chosen to reward maximum clustering with slightly higher intensities. We believe this is the best approach to environmental protection. In this system, floodplains, waterbody buffers, wetlands, watersheds, and drainage way soils (soils that have evolved to their current condition by the presence of water over or through them) are all water-oriented elements. Slopes and woodland or tree protection are overall environmental protection types.

In terms of development, there are a number of environmentally sensitive design strategies, some of which are not currently considered “normal.” Others may even be prohibited. This includes environmental regulations designed to make buildings more sensitive. The “green roof” is just starting to get some attention in the United States, but is heavily used in Europe. Large, flat-roofed buildings are logical candidates for these roofs and the Town could mandate their use or penalize uses that do not. The design of storm water systems in Chapel Hill uses standard engineering practices that substitute pipes for natural channels. The pipes move water faster, increasing flooding; are costly to build and maintain; and can only carry a limited amount of water, thus relying on streets or other areas to carry storm water flows in larger storm events. A natural system is cheaper and creates better water quality. The Town can mandate maximum use of surface drainage, linked detention, enhanced floodplains or stream channels, and individual water gardens to make a better system. It can also review the normal grass lawn approach to landscaping. Environmentally, native grasses and woodland vegetation are far better surfaces than lawns. Where lots are large enough, there should be incentives or requirements for natural surfaces.

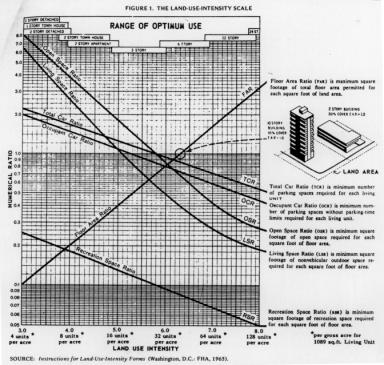

Land Use Intensity (LUI) System. Chapel Hill is unique in using this system[3]. Other communities that used this system have abandoned it in the past.[4] The LUI system has three problems. The first is its complexity; the second is its lack of user-friendliness; and the third, and most important, is its weakness in achieving Chapel Hill’s goals. The current code uses four different measures for determining whether a development meets the LUI value for the district: floor area, outdoor space, livability space, and recreation space. Each category must be measured to determine if a project meets the standards, and the resulting LUI number is not intuitively meaningful.

Most important, the system does not clearly relate the LUI measurements to specific community objectives. Chapel Hill is very concerned with neighborhood community character. The LUI system was developed as a means of evaluating development in the 1960s. It consisted of a graphic system on which each of the measures was displayed as a curve. The LUI numbers were vertical lines (see Figure 3) so that the values of the curves where the LUI number crossed the curves were the values used. Chapel Hill created its own numbers, but there is no master curve system to document its creation, and staff indicates that the numbers have been adjusted several times. Additionally, the numbers do not relate to either resource protection or affordable housing, important goals identified by the community. One option would be to try to clean up the LUI system and document it. However, there would still be a lack of user-friendliness, and a lack of connection to community goals.

|

There are two other options for addressing land use intensity without using the LUI system. Both are performance oriented. The first has been used in performance ordinances around the nation for over 25 years and relies on two measures. For residential uses, the two measures are density and open space. For non-residential uses, the two measures are floor area ratios and landscaped surface ratios. What is especially useful about this system is that density and open space measures are excellent indicators of community character, and can advance environmental goals. These measures are also more clearly understood than the outdoor space, livability space, and recreation space in the LUI system. Table 1 shows how several existing zoning districts might be converted to a performance standard system.

Table 1. Performance Zoning Example |

|||||

|

Use Description |

Minimum Open Space Ratio |

Maximum Gross Density |

Maximum Net Density |

Maximum Impervious Surface Ratio |

Lot Size (acres/frontage) |

|

R-1 17,000 GLA 80-ft. wide lot, equals gross density of 2.56 |

|||||

|

Single-Family |

.10 |

2.56 |

2.84 |

.248 |

9500/80 |

|

Cluster |

.24 |

2.56 |

3.45 |

.222 |

8000/70 |

|

Cluster |

.37 |

2.56 |

4.41 |

.185 |

6000/60 |

|

R-2 10,000 GLA 65-ft. wide lot, equals gross density of 4.36 |

|||||

|

Single-Family |

.10 |

4.36 |

4.87 |

.324 |

5400/55 |

|

Twin |

.26 |

4.36 |

6.30 |

.201 |

4500/45 |

|

Town |

.58 |

4.36 |

11.22 |

.240 |

2500/25 |

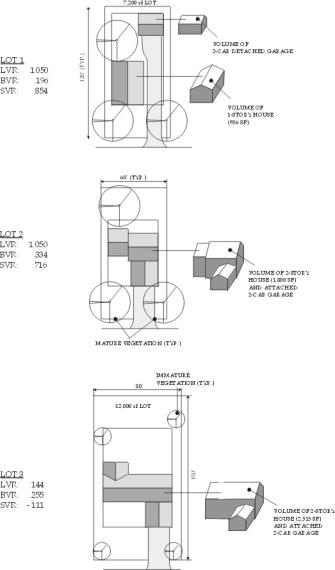

The second system available is also based on community character analysis. However, this system not only looks at two-dimensional land use measures, but at the third dimension of building and landscape volumes. It is based on observations of community character over time and the results of community preference surveys that rate how the built environment (buildings, streets, parking, etc.) interacts with the landscape (either that planted by the developer or that protected during construction). It relies on two principle measures, a building volume ratio and a landscape volume ratio (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Building Volume Ratio (top) and Site Volume Ratio (bottom)

|

The building volume is the volume of the building, parking, loading, and exterior storage. This includes all the elements that have measurable impact on the character of the development. The landscape volume measures the landscaping, including new material and elements of the existing landscape that are preserved. These two ratios can be combined into a single measure, the site volume ratio (see Figure 6), which is the building volume ratio subtracted from the landscape volume ratio. A positive value indicates that there is more landscape volume than building volume; a negative value means that the building volume is dominant. These measures can be related to community character in that the more urbanized an area is, the more building volumes it will have. These examples of an urban development and a traditional streetscape illustrate the concept.

|

Both of these systems have an advantage over the LUI system in that they can be used to model impacts of proposed development. Computer models can measure and meaningfully link a large number of values, without having to specify them all in a regulatory format. Density, open space, building coverage, floor area ratios, impervious surface ratios (landscaped surface is its obverse), landscape volume ratio, building volume ratio, and site volume ratio can be tracked and used to evaluate a project’s impact on resources or ability to meet the community goals. For example, open space and impervious surface measures permit precise analysis of the impacts of a proposed development on water quality or run-off. Open space indicates land available for protecting sloped areas, forest cover, or other areas. Both measures have demonstrable relationships to community character. For all of these advantages, we recommend that one of these two measures be used in place of the LUI system.

Affordable Housing. Maintaining a stock of “affordable housing” is one of the most difficult tasks before the Town. Before beginning this discussion it is important to define what we mean by affordable housing. There are two types of affordable housing: market rate and subsidized. Market rate affordable housing is low-cost housing built by developers for profit. In general, affordable market rate housing is rental housing at high densities, and mobile homes. These are smaller units at a higher density, with lower per-unit land, material, and infrastructure costs, keeping construction costs low. Subsidized affordable housing includes a governmental program that lowers the cost of housing, either directly through government infusions of cash or indirectly as in the tax credit program. Zoning can have the most impact on market rate affordable housing. In terms of subsidized housing, zoning need only ensure that it does not throw roadblocks in the way of its construction.

When planning for all types of affordable housing, the Town should avoid building “projects.” Concentrating affordable housing in tall buildings or clearly identifiable areas has been proven to be counter-productive, both for the community at large and the immediate residents. All affordable housing should be integrated into the community to the maximum extent possible.

Many strategies are important to making market rate housing more affordable. In general, affordable housing will be at the low end of the market size range. Single-family housing built during the depression or right after World War II was often in the range of 1,000 square feet per dwelling. Today, the average unit is more than twice that size. Housing costs are figured on a square foot cost, so the smaller the unit, the more likely it is to be affordable. Thus, a series of strategies to encourage smaller units should be considered. Maximum floor area ratios can create a maximum house size for a lot. For smaller lots, maintaining a lower size will maintain a stock of less expensive homes.[5] A control on building size will also impact land costs because the banking community expects the land to be in sync with the home value.

Again, this should not mean the creation of concentrated districts for low-cost housing. To create diversity within a community, the size of homes should vary at a very fine scale. Zoning with a minimum lot size has traditionally meant that all the lots were close to the minimum. Traditional communities had variety on the block level. This can be brought back under the average lot size form of zoning district. Instead of having a minimum, the district requires three lot sizes: small, medium (the district average), and large. Each block face would have to contain all three. If combined with floor area ratios, the inclusion of small lots will result in smaller, less expensive dwelling units.

Chapel Hill defines three residential use types: “single- family,” “two-family,” and “multi-family,” but there are actually four distinct types, with the addition of “single-family attached.” Each of the four types can contain a number of different styles. Specifically providing for all the styles can provide more options for the market to consider.

The single-family types can be divided into five types: conventional single-family, lot line, village or traditional, zero lot line or Z house, and patio house. There are several forms of two-family: twin (side by side), duplex (over/under), cottage (separate building to the rear) and accessory dwelling. The latter, the accessory dwelling, is clearly classed as a two-family unit, but there are advocates of small accessory apartments being considered as single-family. Attached single-family house types include the town or row house, the atrium house (one-story row), and multiplexes, which are similar to town houses, but where units are not floor to roof. In addition, there are a wide range of town houses and some special housing types. Three-story town houses, duplex town houses, and roof deck town houses are higher-density town house type solutions ideal for mixed use or traditional community designs.

Providing for a diverse palette of housing types (see Figure 7) encourages greater variety. In planned developments, a minimum mix of housing types can result in more diverse housing. Special housing types can also be designed for more diversity: for example, elderly housing with less parking and higher density focuses on one particular market segment. Smaller units designed for very high density (one- or two-bedroom units designed for low impact on neighboring properties) can be used to reach the lower level of the market because land costs and building costs are lower.

The last issue is whether the controls are voluntary or whether there are mandatory percentages of affordable units. While the voluntary controls seem on the surface to be the best approach, it is difficult to achieve significant utilization. Builders and realtors fear that the affordable units will lower home values. As a result, even when significant bonuses are given, they are often unused. The opposite approach, punitive rather than incentive (lowering the density if there is no affordable housing component), has to our knowledge never been tried. Whether it would work better than the bonus because it is a penalty is an unknown. The mandatory provision takes the guessing out of the equation, as every developer has to comply.

In sum, because the demand is so high and prices are increasing, we believe all of these techniques will need to be used to address the issue of affordable housing.

|

Review Process |

Mixed Use |

Conservation Design |

Neighborhood Protection |

Parking |

Other Design Issues |

|

Simplify Shorten Time Frames Require More Visual Materials Make less adversarial Keep Concept Plan Make more things “minor changes” Make changes to encourage small businesses |

Encourage mix of uses in most developments Encourage / require a residential component Allow on small parcels Avoid possibility of a bar next to a church Allow retail uses in existing residential neighborhoods |

Minimize growth of impervious surfaces Strengthen tree protection regulations More rigorous stormwater management controls Re-think restrictions in floodplains, RCD, to better protect Emphasize open space Protect steep slopes Re-think cluster provisions Study sedimentation, erosion control requirements |

Expand restrictions on front-yard parking Create targeted standards that reflect existing conditions in older neighborhoods Revisit non-conforming provisions for older neighborhoods Consider occupancy limitations, rental licensing Consider noise, lighting standards |

Consider maximums Encourage shared parking arrangements Consider provisions for overflow parking on non-asphalt surfaces Consider eliminating parking requirements downtown More use of payment-in-lieu of parking How to make Transportation Management Plans more effective? Require more plantings in parking lots |

Address road connectivity Reconsider street design standards Add Bike, sidewalk standards Use mechanism other than Land Use Intensity System to regulate density, open space Use incentives to get better design Reconsider buffer requirements

Require more open space if land is steep or wet Reconsider recreation requirements |

[1]There are two reserved articles that are numbered, but not currently used.

[2]Center for Watershed Protection, Rapid Watershed Planning Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide for Managing Urbanizing Watersheds. CWP: October, 1998.

[3] There seems to be a myth that the LUI system was borrowed from Performance Zoning. In fact, performance zoning was begun in reaction to developments done under the LUI system. The LUI system was developed by HUD and the curves were plots of existing developments.

[4]A number of local governments in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, abandoned the LUI in the early 1970s. The consensus was that developments under the LUI were unattractive.

[5]Typically, the house is 3/4 to 2/3 the cost of the final product, with land being 1/4 to 1/3 the total cost.